I recently had an interesting Twitter exchange with my friend Dan Munro over at Forbes regarding a KevinMD posting, Quality is a Word that Lacks Universal Meaning. The article touched on one of my book topics: the industry’s reporting-centric, manufacturing-oriented conceptualization of quality is ambiguous and unreflective of the problem space. We need to look at quality differently.

I recently had an interesting Twitter exchange with my friend Dan Munro over at Forbes regarding a KevinMD posting, Quality is a Word that Lacks Universal Meaning. The article touched on one of my book topics: the industry’s reporting-centric, manufacturing-oriented conceptualization of quality is ambiguous and unreflective of the problem space. We need to look at quality differently.

Dan raised the concern of data — do we really have the data to support a different view of quality, especially in light of resistance to data collection?

Dan is absolutely right; from a quality perspective, we often are “flying blindfolded and handcuffed.” But do we really lack data?

Consider that most health organizations have four available data sources:

- Their own data (though it is often not readily consumable)

- Partner data (though they may not be sharing it)

- Purchasable data (though we often just pay for the answer, not the data)

- Public data (though we often can’t determine how best to use them)

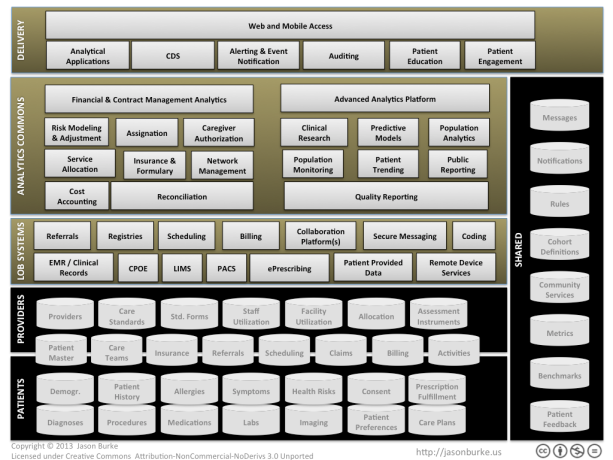

Between these four categories, we are drowning in data: EMRs, claims, referrals, device, billing, CMS, labs, imaging, clinical trials, public health, service utilization, reimbursement, health exchanges, costing, genomics, consumer sentiment, behavioral data, consumer health devices, e-prescribing… and it keeps coming. It doesn’t look to me like we lack data; it looks like we lack insight. So why do we lack insight?

Part of the challenge is focus. Instead of getting smarter on how we use data, we continually shift our attention to the next set of data we need to collect, the next regulation we need to satisfy, the next benchmark we are handed, the next incentive to capture or penalty to avoid, the next dashboard report to build.

A second challenge is lack of process oversight, which I think validates Dan’s question. We have plenty of processes across health care, and we do manage them. But we fail to instrument or otherwise empirically characterize those processes in such a way as to offer process-related insights. Note that meaningful use and HEDIS don’t do this either — they simply establish benchmarks. Additional instrumentation does not imply we must collect more data — we could use derived or surrogate measures, for example. But it just needs to be a focus (see above).

But a third challenge is the litany of status quo excuses that leaders hear daily about why we cannot be more data-driven in our decision making:

1. We don’t have enough data.

Of all the data excuses, this one gets the most play. There are two assumptions behind this state. First, it assumes that a complete inventory of data options exists, and that inventory does not offer enough to do what you need. In my experience, most firms do not have a handle on all of their data options, and they do not understand (because they haven’t looked analytically) whether a given data asset is useful in understanding the problem at hand. There is also an assumption you can determine how much data you need without analytics – which is untrue. You actually need to do an analysis to determine if you have enough data.

2. The data we have isn’t good enough.

This excuse always interests me because, 99% of the time, it surfaces without any actual analytical work being done. The data isn’t good enough…good enough for what exactly? The perception is usually derived from either a) previously struggling with the data on an unrelated project, or b) physically looking at the data, which often appears messy, incomplete, and/or error prone. Yet all data assets have limitations such as these; the utility of data can only be assessed in the context of the question being asked and the analytical method being used. And the data never gets better until you use it and make it better.

3. The data exists, but we can’t have access to it.

Our obligations to patient privacy notwithstanding, we have to move beyond the rampant fears in using data. Rules and contract terms should not prolong patient suffering and/or drive up health costs. If an organization has data assets that cannot be used for agile innovation, then change the rules, re-write the contracts, change the consent forms, or provision new data sources to compensate.

4. We can’t use the data because of regulations.

This excuse is really a variation of #3, but it has the apparent added weight of the government behind it. My same opinion applies. There is no question that we need strong data protections and use provisions — we’ve been facing that for decades. But no patient I know would rather suffer, die, or face bankruptcy than have their data used responsibly to improve medical decision making. And if they do, that is fine, but have the patient or sponsor “opt out”, not “opt in.”

5. The data is not structured in a way that is useful; it would take too much time.

So it is too much work to innovate? If you do not have easily consumable data assets, then maybe it is time to start treating data and analytics more seriously. It is possible to create meaningful, agile analytical assets and insights, but it doesn’t happen accidentally, and it doesn’t happen without work.

The hard part of these five excuses is they all hold an element of truth to them. But when we accept those challenges as barriers, we don’t progress. And to Dan’s point, there is justifiable, growing resistance to performance metric pile-on. Most practitioners I know do not believe there is a strong association between existing quality measures (MU, HEDIS, etc.) and real-world, patient-centered outcomes and costs. And though that conclusion is overly broad, I think there will be growing evidence to support that view. For example, two recent studies — one in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, another in Health Affairs — call into question the association between readmission rates and quality.

The fact that we are using data inadequately does not mean we should not be using data. And it doesn’t mean we need to re-double our efforts around meaningful use and physician education. It means we need to become smarter about the questions we ask, more focused in the priorities we set for our organizations, and predictive through the tools we give practitioners and patients to make more informed decisions.

In my opinion, we should be building and deploying comprehensive, predictive quality models that we know improve outcomes and costs; not justifying retrospective metrics that we hope might help.

You must be logged in to post a comment.